Scotland’s Duncan McLean knows more about Texas swing than most Texans; it’s an avocation, a pure-hearted love of the form, that sucks up much of the Aberdeenshire-born author’s time. McLean now lives in Orkney, an isolated island chain off the Scottish coast. When he’s not packratting around the mainland in search of golden-age swing recordings or playing with his own outfit (the Orkney-based Smoking Stone Band), he plies his vocation, writing what he terms “disturbing, disturbed novels” like Bunker Man and short stories like those collected in Bucket of Tongues.

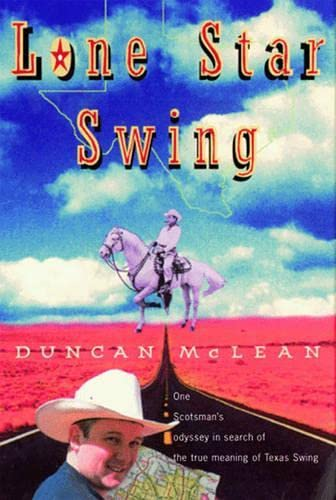

McLean won a ’93 Somerset Maugham Award for Tongues, and he funneled the prize money into research — six weeks and 10,000 Texas road miles’ worth — for his new book Lone Star Swing, a nonfiction piece about . . . well, the subtitles say it all: The one on the jacket reads One Scotsman’s Odyssey in Search of the True Meaning of Texas Swing; the title-page ‘title is On the Trail of Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys.

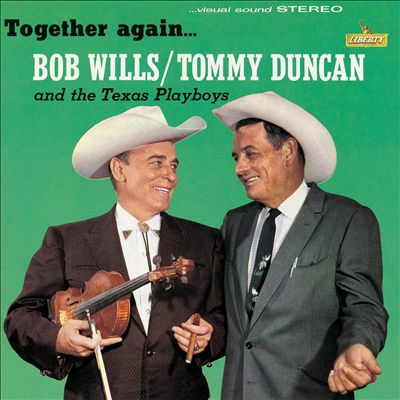

Ah, Wills — or “AH-haaaaaaa,” as the fiddle-sawing bandleader used to holler when one of his Playboys hit just the right note(s). The late western-swing godhead from the Panhandle town of Turkey casts the largest shadow in McLean’s melodious, enchanting piece of time-travel writing, which delves deep into the heart of Texas’s musical heritage. It’s a past that’s been almost, but not quite, obliterated.

Between lovely digressions and Lone Star adventures — Harley riders gaping at the Marfa Lights, heatstroke and scallions at the Presidio Onion Festival, a hit-and-run accident in the parking lot at Austin’s Broken Spoke roadhouse that left McLean’s “Hertzmobile” better ventilated than before — the author spins tall (but true) tales about contemporary encounters with swing survivors.

There’s Roy Lee Brown (of Milton Brown’s legendary Musical Brownies) playing with a nursing-home pickup band, a jaw-droppingly comic phone convo between the Scot-brogued McLean and stone-deaf Floyd Tillman of Houston’s Blue Ridge Playboys, a visit to Turkey to see the real deal — the Texas Playboys — at the tiny town’s annual tribute to its most famous son, whose own vocation was cutting hair at Turkey’s still-extant Ham’s Barbershop before his avocative love of music led Wills to the big time with standards-to-be like “New San Antonio Rose” and “Faded Love.”

We interviewed McLean via e-mail from his Orkney home.

HP: What do you think about Bob Wills as a musician and a bandleader? And about the man himself? He couldn’t play the fiddle well, couldn’t sing to save his life, but what an ear — and a musically open mind — he had. I’ve always thought Wills’s strength lay in arrangement and the assembly of top-drawer talent to bring the arrangements to life. And that he was, in a sense, a benevolent dictator — and a benevolent thief.

McLean: I agree completely. He was very limited as a fiddler, but a truly inspired bandleader. As is often the case, his leadership mixed generosity and sentimentality with hard discipline and a fair bit of dictatorship. A classic patriarch. Happily, he was never a dictator in a musical sense. All the musicians I’ve talked to emphasize that he encouraged them to play what they wanted as long as they played it with all their heart. That’s what made so many of the versions of the Texas Playboys so good, and why so many musicians have fond memories of him despite his drinking, temper, depressions, etc. Having said all that, I’m very glad I was never married to him.

HP: Drawing from the cover title of your book, what, for you, is the “true meaning” of Texas swing?

McLean: Western swing was the dance music of the Southwest through the ’30s, ’40s and up to the mid-’50s. To an extent, anything that anyone was dancing to in that period could legitimately be called western swing. In this most general sense, western swing was just the pop music of the day, with a flavoring of Southwestern influences — e.g., more fiddles than in the Northeast, occasional cowboy themes or lyrics, Mexican influences, big blues elements.

By the early ’50s, pop music was changing so much — into rock and roll, of course — that the Southwestern slant on it didn’t end up as western swing, but rather honky-tonk, Lubbock rock ‘n’ roll — Holly, Orbison — Southern rock, Austin singer/songwriters, outlaw country music, Stevie Ray Vaughan rocky blues, etc. People can and do play western swing now, either ’cause they played it in the ’40s and ’50s, still love the style and see no reason to change — the continuing Texas Playboys, the Original River Road Boys out of Houston — or out of a conscious/self-conscious love of the sound of the music, and a desire to play it, to revive it, to spread it to a younger audience who’ve never really heard it. And here I’m thinking of bands like the Rounders in Dallas and the Hot Club of Cowtown in Austin.

Having said all that, the “true meaning” of Texas swing might well be not all that historical stuff, but rather an attitude. To an extent, I’d be welcome to call almost anything Texas swing as long as people can dance to it, drink to it, laugh to it, and as long as it has that openhearted welcoming of musical influences from the cultures that surround it.

HP: From your perspective as an outsider, what factors make Texas such a hotbed of music?

McLean: I think what made — and makes — Texas such a hotbed of musical creation is the movements of population. What a glorious hodgepodge of peoples, cultures and musics from all sorts of places. Need I enumerate them? How about Scottish, Irish, German, Czech, Mexican, Spanish, African? I think there are “officially” 26 important ethnic and cultural inputs into modern Texas. What a wonderful mix! It explains so much about your state in all its aspects, including its restlessly creative music scene.

HP: Any feelings or conclusions about Texas that didn’t make it into the book? Specific memories of Houston?

McLean: I regret to say that Houston was the one major city I didn’t visit on my trip in ’95. I simply ran out of time before I got there. On subsequent trips, I have met some of the folk I would’ve liked to meet in Houston: Cliff Bruner, Clyde Brewer, Shelly Lee Alley Jr. Great guys, great musicians.

Texas is too big and too diverse to come to any snappy conclusions about. In a way, the whole book is my conclusion about Texas. I hope it comes across clearly that, despite moments of boredom, bafflement and fear, I loved my time there, and many, many people I met.

HP: Do you think we’ll ever see a full-blown western swing revival? Most people, even here in Texas, don’t have a clue who Bob Wills was, never mind Milton Brown. And what do you think of someone like George Strait, who, in his mainstream, tight-jeaned way, honors the music of Wills and Brown and at least keeps its spirit alive?

McLean: George Strait is okay. I have quite a few of his records, and enjoy them, though they do tend toward the bland a bit much for my tastes. I do wish that Strait would use some of his millions to pay for recording sessions by, or reissues of, or books about, or concerts featuring, or pensions for some of the great names from the heyday of western swing. That would represent a real contribution to the culture of his home state.

I’m fairly optimistic, in a small way, that the music is slowly getting more and more serious recognition. But I don’t think there will ever be a full-blown revival, because the particular social and cultural forces that allowed and encouraged western swing to emerge in the ’30s have all disappeared or changed. I just hope that we can remember and honor and occasionally revisit this great music of the recent past — as we do with, say, New Orleans jazz.

HP: Do you have a favorite western swing track? If yes, why?

McLean: I could name a hundred, but off the top of my head, I’ll go for the Texas Playboys’ “You’re from Texas” from the Tiffany Transcriptions. One, because it’s got a tremendous, driving beat; two, because [vocalist] Tommy Duncan gets the words wrong at one point and Wills cracks him up with his wisecracks; three, ’cause I like the way it welcomes in the “stranger” and declares him/her a fellow Texan. Hey, it’s almost as if I’m being declared an honorary Texan — for the duration of the song, at least.

HOUSTON PRESS APRIL 16, 1998